The Shield Wall on El Capitan

Written by Peder Ourom

Read on or Listen in!

El Capitan Yosemite California,

The Shield Grade 6, 5.9 A4

First ascent: 1972 Charlie Porter / Gary Bocarde

10th Ascent

November 1979

Canadian Team: Paul Berntsen, Peder Ourom, Ward Robinson

The Zodiac, The Shield, Mescalito, and Tangerine Trip were the best wall routes in the 1970s, and the most coveted. These routes had one thing in common, they were first imagined and climbed by Charlie Porter. The Zodiac, The Shield, and Mescalito, climb up the steep overhanging SE side of El Capitan, the aptly named Crazy Wall. Tangerine Tip ascends the amazing Shield headwall to the left of the Nose route. Charlie established 2 of these routes in 1972, and 2 more in 1973. Two years later he added a fifth major route, Excalibur. It was rumoured to have mandatory 5.11 Off width sections. That one we didn’t even talk about.

All of these five routes were incredible climbs. In the mid-seventies, he also soloed the Cassin Ridge on Denali, was the first to climb the famous Polar Circus ice route in the Canadian Rockies, solo climbed the monster 4000 foot face of Mt. Asgard on Baffin Island (a 40-pitch route that took 9 days after weeks of work). It’s also the cliff Bond skied off in The Spy Who Loved Me with a British flag on his parachute.

In the following 20 years, Charlie solo kayaked in Patagonia, and became a leading scientist and expert on oceanography and climatology in the region. He passed onto his next adventures in 2014.

In the recent films and stories of this climbing era, including Valley Uprising, Jim Bridwell is often built up as being the most amazing wall master, with the best eye for a new route, who is able to lead the hardest and best new routes. With no disrespect to Bridwell, this is not the truth. He was a master of creating difficult aid pitches using newly designed gear in unique ways, and moving the rescue team forward. He did establish one exceptional new route, the Pacific Ocean Wall, and it was a difficult technical masterpiece for the time. The truth is, Charlie had the best eye for a line and picked them out from under Bridwell’s nose.

Charlie Porter’s climb of the Shield, established with Gary Bocarde in 1972, was a masterstroke of genius. Following a beautiful series of thin overhanging cracks between the Salathe and the Nose routes, the A4 route was thought to be pretty much impossible to retreat from. The Groove and Triple Crack pitches featured sweet RURP (Realized Ultimate Reality Pitons), and Knife blade placements. Originally called the Windshield, it is one of the most amazing places on El Cap. To climb The Zodiac, The Shield, Mescalito, and Tangerine Tip in 2 years was my dream. With a no-falls ascent of the Zodiac already accomplished in the summer, The Shield would be my 2nd major El Capitan route of the year. The plan was for Mescalito and the Tangerine Trip the following year.

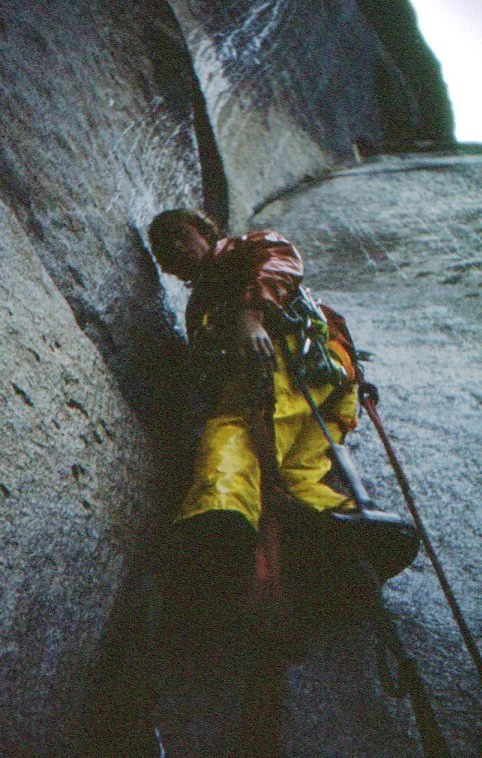

Paul Bernsten climbs the Shield Wall, El Capitan, Yosemite, California, 1979.

It was too late in the season, and we knew it. Most climbers had already left, the Americans heading farther south to Joshua Tree, and the Canadians back north to start earning the required weeks toward their next EI Cap claim. Both Ward Robinson and I had spent the season doing the regular valley hang, for the most part working on improving jamming techniques on the smooth cracks down at Reeds Pinnacle, Arch Rock, and The Cookie. Our favourite face climbing was on Middle Cathedral (we hadn’t really discovered Tuolomene yet). The choice routes were the easy multi-pitch routes such as The East Buttress of Middle, the centre Pillar of Frenzy, and the NE buttress of Higher Cathedral. We were pretty average free climbers, and knew it. But we were slowly getting better. Ward in later years became a loose rock master, climbed the North face of The Eiger, and soloed Slipstream on his 60th birthday just to make sure that he had not aged.

The highlight and focus for each season however, was not free climbing, despite most of our days being spent finding short routes within our capabilities. We spent many lazy afternoons down by the Merced River after completing an early morning free climb. Hanging and observing from the back of El Cap meadows, watching clouds race by, and trying to decide the next big wall objective. One big wall a year was good, but if you could climb 2 and get photos it would even better. The goal was to have a solid story at the annual John Howe slide show.

As far as big walls go at this time, the Canadian teams were as strong as the American teams.

Following in the footsteps of Steve Sutton, Hugh Burton, Eric Weinstein, and Darryl Hatten, our generation was well trained in Squamish, and had a skill level that many Americans lacked. On a later epic adventure on Mescalito, I was shocked at American Walt Shipley’s lack of wall climbing skills. Watching him switching from aid to free a couple of moves, and then abandoning the free to get back into his aiders, again and again, I just shook my head. My Darryl trained technique was more slow and methodical. To be fair to Walt, I should at this point mention that some of these moves, up on the nice hook ledges, were very close and sometimes the same as the holds on what was to become Tommy Caldwell’s masterpiece the Dawn Wall free. We all knew Walt was wired a little differently than the rest of us.

By the end of October, we had picked the Shield for my second wall route for the year. As it was very late in the wall climbing season, we were also avoiding the late spring and summer crowds that gathered on the bottom slabs of the Salathe Wall on their journey up to Mammoth Terraces. For us to get to the start of the Shield, we would need to climb the first 10 pitches of the Salathe Wall, then the next 10 pitches on the Muir Wall, before ascending the steep roof pitch that turns you into flies on the wall. After committing to this pitch, no retreat would be possible.

As the days were short, and we knew progress would be slow, we decided to recruit a third climber. This is a common tactic on a big wall, the heavy physical work of hauling loads being shared by 3 not 2, and giving you a partner to talk to at belays that could and would last for hours. You also needed a 3rd climber that had a gear rack, in order to make the route possible. So here Paul Berntsen came into the picture. He was a fellow Canadian and experienced mountaineer, and was fit and motivated to join forces with us. The three of us Canadians formed a great climbing team.

A little drawback however, was that Paul had never climbed a big wall.

This did cause Ward and myself a few concerns, as the Shield was one of the hardest aid climbs in the world at the time, but at least he could help haul, belay, and entertain, as Ward and I did the bulk of the leading.

With the gear sitting in a huge pile, on the site picnic table, the big sort was on. For the most part, these sorts are pretty standard. Thread your Jumars with new webbing, squish extra clothes very tightly into stuff sacs, line the haul sacs with thin sleeping pad, rinse out the toxic bleach bottles for their conversion to a water bottle, that sort of thing. One final chore would be sorting and organizing the food. This time, we chose to have two big equal stuff sacs full of food, for three people, for the expected one week climb.

At this time a little error was made. The food stuff sacs should each have had an equal portion of day snacks, and the real sausage and cheese kind of food that feeds the huge work loads. Unfortunately, we packed one full of snacks, with the other holding the real food. We would regret this bitterly in the coming days. The gear weighed around 400lbs, consisting of three haul bags, and two small daypacks. With a pitch fixed, everything organized, weather reports checked (no possible way they could forecast a week in advance), and many cans of nasty Colt66 beer later, we were ready to commit.

The start of the Salathe goes up a couple of pretty nice, not so hard cracks, with the Shield looming massively 2000 feet above you. Arguably some of the nicest pitches of the Salathe wall route, it was great to get started, although the massive loads that needed to be hauled slowed progress to a crawl. A few pitches higher, and we were at the base of the half dollar, a distinct feature that featured an awkward and flared right leaning chimney thrash, and for the first time on the climb it looked like a hard lead. Like the pitch leading to Camp 4 on the Nose, these pitches are much easier as free climbs, but with the clunky Royal Robbins boots, and a massive gear load, this was out of the question. Often, it’s all you can do to get the next piece of gear 12 inches higher as you cram yourself in the back of the slot.

It was Wards lead, and it didn’t go well. Thrashing and flailing is the style he used, accompanied by massive swearing. He was hating it. It took Ward hours, and pissed him off so badly, that at the evening’s bivouac, on the top of Mammoth Terraces, he decided to quit climbing forever, and leave us (we were 1000 feet up the climb). This was a surprise, but he could not be persuaded to stay, and Paul and I could not be persuaded to leave.

The conversation was intense as we attempted to convince Ward to continue on with us up onto the Shield.

Ward’s decision was to escape the route and abandon us. Not by untying and jumping, but by knotting all our ropes together and rappelling 300 feet down to the Heart Ledges. From the Ledges he had spotted a fixed line running down another 1200 vertical feet and slightly sideways to the ground. He waved up, all good to go, pull your ropes up, see you later slowpokes. We had lost most of a day getting reorganized, and this cost us dearly high up on the route. I was concerned that we had lost Ward for the route, but figured what the hell, if necessary, I could lead all the pitches. Paul was still motivated, and this was what was most important. We disappeared around the corner and that was the last we saw of Ward.

After getting organized on the huge Heart Ledge, Ward then prepared to descend the fixed lines down to the ground. Unfortunately, his descent did not go according to plan. To his surprise he realized that the ropes were fixed tightly down the cliff face, and it would be impossible to get a rappel set up on the rope. He would need to inch his way down the ropes using his Jumars, although they are designed to go up not down. Each dangerous unclamping of the rope, would only let him descend perhaps 4-6 inches. It was going to be a long, slow, and dangerous retreat.

I should tell you now that Ward was a very experienced climber at the time. His “spidey sense” was tingling. We were way behind schedule, and moving super slowly, three pitches a day. The hauling was fucking brutal, up the low angle slabs. We were looking at 8 or 9 days, not 7. The weather could not possibly hold. One final detail of Ward’s descent would be realized by us that night. Ward had taken the stuff sac of real food down with him, maybe even by mistake. We only had a half-full bag of snacks for food, for the next undetermined number of days. We were going to be hungry. For the next two days and nights, we continued crawling up the Muir wall section of the routes.

The short days were hitting us hard, and it is for this reason long and technical walls were rarely climbed at this time of the year. It would be a very cold and exposed place for two days on the overhanging 1000 foot high Shield.

We had El Capitan to ourselves for the most part, with the occasional party, off to the right on the Nose, barely in sight. They were always moving quickly, on the easier ground of the Nose. We had now arrived at the base of the Shield, at the commitment point of the climb. A massive overhang loomed above us, with the route traversing to the left, and then continuing onto the actual Shield. We could have escaped at this point by going right to the Nose, and considered it, but looking into each others eyes we saw that our eagerness to climb the Shield had not abated. We would go for it.

The weather made us nervous. It was perfect, but we knew that our chances of making it up the exposed wall without a storm in the late fall were poor. We had no cover for our handmade ledges and hammock, very poor raingear, and a mix of clothing that did not include the latest pile jackets made by Chouinard Equipment.

Paul Berntsen traversing left and committing to the Shield Wall. El Capitan, Yosemite, California. 1979.

I coached Paul as he traversed left to the start of the committing roof pitch. Paul was eager and enthusiastic and was loving it. The start of the pitch was the crux. Paul aided carefully using pin stacks, hooks, RURPS, and copperheads. All for the first time, with subtle coaching from the belay. Above us loomed 1000 feet of smooth unbroken rock, slightly overhanging. As the sun set, we hustled to prepare our ledge, our home for the night. The bivouacs so far had been on rock ledges, with the portable ledge as a supplement. For the next two days, it would be the only ledge, and become the centre of our universe. As the sun set and the winds dropped, the agile swifts came out hunting, proving that they were at home here and we were not.

Continuing up the route. The Shield Head Wall, Triple Cracks Pitch, El Capitan, Yosemite, California. 1979

The following morning, Day 5, we continued up the route. The groove and the triple cracks had only been climbed a handful of times since Charlie’s first ascent, and were still pretty much undamaged. Hundreds of ascents later, piton damage resulted in these cracks being completely destroyed. For us, they were pristine Knife blade-sized cracks. By now, we really were getting used to the exposure. Down ceases to exist when it is no longer an option. The afternoon winds were so strong that we hung a few heavy pitons on the bottom step of our aiders, to stop them blowing sideways when we attempted to step upwards.

The bottom of the cliff was a long way down, and we had launched out into space.

Suspended from the cliff like bats is a pretty much impossible place to retreat from. We were climbing a series of thin discontinuous cracks that snaked up the wall. On the sixth day we crested the smooth Shield wall, and stood on our first rock ledge in two days. By now we were starving, as the real food sac had exited the wall with Ward who no doubt was now watching from the meadow below, snacking on cheese and sausage. Finding a small bag of M and M candies at the bottom of a haul bag, we doubled our remaining food supply. Chicken Head Ledge, aptly named, is about 400 feet below the top of El Capitan. It was quite the relief to be able rest and organize on a real rock ledge. Paul fell asleep quickly, but this was not a night of rest for me. Off toward the west, in the last light of the day, high stratus clouds had started to appear.

Looking down from Chicken Head Ledge, The Shield Wall, El Capitan, Yosemite, California. 1979

I awoke Paul at midnight, insisting we get a move on now. We could both feel the arrival of a storm front, moving quickly toward us from the coast of California. By now It had blocked the moonlight, and the winds had started to pick up. It was a relief to be above the section of the climb where we would have been completely exposed to the elements, however we were still in peril with one day of climbing left.

Our concerns about the approaching storm were increasing by the hour, and our good weather window had disappeared.

We knew it would be tight race to get off before getting hit. I lead the pitch off Chicken Head Ledge in the dark, and Paul led the next pitch in the early hours of the morning. We had covered about half the distance to the top, and were now about 200 feet below the summit of El Capitan.

Tucked under a tiny roof, Paul put me on belay as I traversed out and left into the tempest. In dry conditions, this final free pitch up a shallow chimney would almost be fun. Unfortunately for me, the holds were covered in 3 inches of ice. A stream of icy water that ran off the summit was freezing on contact with the ice that had covered the cliff top, and also froze all over me and the equipment. Carabiners had to be hit with my hammer to open them, and the rope increased in size to the point where I had to beat the ice off the rope continually as it froze to the rock. To complete the pitch would require every ice and aid climbing skill that I had, and a few that I did not have.

Peder Ourom climbing the last pitches of the Shield Wall in icy water. El Capitan, Yosemite, California. 1979

Our survival now depended on me somehow making it to the top of the pitch.

I took all the rope with me and led the pitch solo style, with the huge weight of the frozen rope hanging off my harness. Knowing my climbing history, I was not going to risk a frozen rope Eiger epic. Mixing free climbing on chopped little holds, with terrible copperhead placements hammered into very marginal shallow seams, I reached the top of the steep wall and was just below the top of El Capitan, just below the top little overhang that is the final obstacle. I had been climbing in the icy groove for around 6 hours. The route now traversed up to the right, somewhere. It was completely covered in snow and ice. I hunted for the belay crack by sweeping off the snow and chipping away the ice, without any luck.

Clawing and scratching, about 3 feet below the belay, I fell. Sliding and tumbling in a huge arc, I hammered back down into the ice and water funnel that I had just climbed. Falling most of the length of the pitch, I ended up 30 feet above Paul, out in space. It was close to a 100 foot fall. There was one benefit. The fall had brought me a lot closer to Paul, and we could finally hear each other screaming. For almost a whole day Paul had been unable to communicate with me, and had no idea what my situation was. Uninjured from the fall, I told him that I would head back up and try to complete the pitch.

It was the lead of my life. It had to be. Repeating most of the pitch with a rope from above, I traversed out across the final slabs for a second time. My little chipped holds had already filled in with new ice. Finding and digging out a little stopper placement helped me tension over right, and I was able to find the belay anchors at last. Pulling up the rope to set up the haul, Paul now knew I had reached the top. The bags caught on the roof of course, so we abandoned them. We would descend with no sleeping or bivouac equipment, and with all our clothing covered in ice. Shivering with frozen hands, we had both finally escaped the Wall.

With night now falling upon us quickly we began our descent. I had been down the descent about 6 times, and considering that Paul had never been here before, I took the lead. Pretty quickly I found the Manzanita Tunnel, a classic spot on the descent that shows you are heading the right way. Soon after, we were at the top of the East Ledge rappels. They were set up at the time for a 2-rope rappel, and we only had one rope left. We would need to use the intermediary rappels. Two pitches from the bottom, as I was leaving a 2-piton anchor, the good piton pulled, and with considerable force I dropped onto the second piton. It was an old ring angle that looked like it could have been placed by John Salathe himself. I continued on the rappel and then we were finally down.

Our two good friends, Ward and Joe, were waiting for us to arrive. They had been waiting impatiently while following our slow progress for the last week, and they had seen us top out at dusk. Upon arrival they were surprised to see that we had no equipment with us at all. Everything we had taken up was still up on the wall. Their escape would need to wait until we rescued all our equipment a few days later.

We turned the heaters in the car up to maximum, and thought we had finished the climb.

We did have a few things to attend to upon arriving back in the Valley. With no dry clothes or sleeping gear, and power wiped out all over the Valley by the storm, we spent the night in the Yosemite Lodge washroom, as the Lodge had emergency generators running. No real heat, but dry at last. We spent the night taking turns pressing the hand dryer, over and over and over again, trying not to fall asleep standing.

The next morning we awoke to a cafeteria line up of over 100 people. Not having eaten in three days, and hammered by the Wall, we looked a little rough. Without hesitation, we cut directly into the line up, in front of the spot where the breakfasts were dished out. Standing there for a minute or two, the server was uncertain what to do. It all came down to the reaction of the next people in line, who had been waiting patiently for over an hour. I locked eyes with a short-haired military or police kind of guy, who stared back at me, glanced at Paul, and then locked eyes with me for the second time. With a little nod of the head, he turned to the server and said “these guys here look really hungry. You better serve them first.”

Days later, after the storm had passed, and the ice and snow had melted, we returned to the top of El Capitan, and Paul did the heart wrenching rappel off the top, in order to clear our haul bags. Finally, finally, Ward and Joe could escape the Valley. With just enough money left for a couple of Denny’s “special” breakfasts each, we headed north to Canada (where the unemployment rate was 30%).

My 1979 wall climbing season was now over.